By Pamilyn Scott

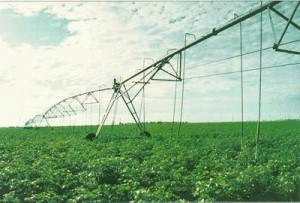

Another method of abating nonpoint source pollution is implementation of a LEPA irrigation system, according to TSSWCB. Drag hoses allow farmers to minimize water use and prevent water and chemical run-off. Photo courtesy of Danna Ryan

Water quality problems have been a concern for several decades. The 1972 Clean Water Act focused on pollution from industrial waste water and municipal sewage. Most of these outfalls were easily identified, and dramatic improvements occurred as they were controlled.

For a long time, it was assumed that storm runoff was essentially “clean” water. This view, however, is starting to change. Rainfall picks up a multitude of pollutants from falling on and draining off streets and parking lots, construction and industrial sites, and farming and logging areas. Eventually, this pollution can flow into creeks and rivers or seep into groundwater.

Nonpoint source (NPS) pollution is defined by the Environmental Protection Agency as “…pollution that does not result from a discharge at a specific, single location (such as a single pipe) but generally results from land runoff, precipitation, atmospheric deposition, or percolation. Pollution from nonpoint occurs when the rate at which pollutant materials entering water bodies or groundwater exceeds natural levels.”

In 1993, the 73rd Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill 503 to help prevent agricultural and silvicultural (forestry) NPS pollution. The bill also designated the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board (TSSWCB) as the lead agency to abate NPS pollution. It further authorized the establishment of Water Quality Management Plans (WQMPs) through soil and water conservation districts and amended the Water Code to grant certified WQMPs the same legal status as Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (TNRCC) point source pollution permits.

Ute Becton installed a drip irrigation system as part of his water quality management plan and is installing the system on an additional 60 acres. Photo by Pamilyn Scott

Senate Bill 503 provides for cost share assistance in designated areas to install approved water quality Best Management Practices (BMPs). Appropriations from the state Legislature are made each fiscal year and are established every two years. More than $2 million are available for fiscal year 1997 which ends Aug. 31.

Through Senate Bill 503, agricultural and silvicultural producers can comply with state water quality laws through traditional, voluntary incentive-based programs. Thus, producers have the opportunity to establish a site specific WQMP that ensures their operation meets state water quality standards. Since June, 1994, more than 1,800 certified plans have been implemented with most of those applying for cost sharing.

“We anticipate an increase in participation as more people learn about the importance and benefits of a water quality management plan,” says Danna Ryan, information specialist for TSSWCB.

Presently, there are 214 soil and water conservation districts in Texas from which anyone may receive assistance in establishing a WQMP. The first step in creating a plan is for a farmer to request assistance from the soil and water conservation district (SWCD) in the county where the operation is located. A producer must agree to become a cooperator with the SWCD if he is not already one, and technical assistance is provided by the SWCD to help develop a plan. Selecting a BMP that suits economical and operational objectives is important for a successful and effective plan. After the plan is developed, it must be accepted by the cooperator, and the Natural Resource Conservation Service district conservationist must certify that the plan meets technical guide criteria. Then the plan is reviewed by the TSSWCB to assure it is consistent with state water quality standards, at which time it certifies the plan.

Certification means an operation is in compliance with state water quality objectives. To remain in compliance with TSSWCB’s voluntary program and receive program benefits, the WQMP must be implemented and operated according to the schedule in the plan.

Not implementing and maintaining the WQMP according to schedule could result in penalties. If a complaint is filed accusing an operation of causing NPS pollution, officials from the SWCD and TSSWCB will make an on- site investigation to determine the validity of the complaint. If the investigation indicates that the WQMP is not being followed and the cooperator fails or refuses to comply, the operation must be reported to TNRCC, the regulatory agency. Depending upon the cause and extent of the problem, TNRCC may levy a fine.

Since a WQMP is voluntary, not all farmers will implement a plan. However, those without a plan also are subject to complaints and investigations. If the complaint is valid, recommendations to establish and incorporate a WQMP may be made. A farmer on which a valid complaint is filed that chooses not to implement a plan, must be referred to TNRCC who may levy a fine as warranted.

“We work to establish WQMPs on a voluntary basis to keep farmers and ranchers out of the regulatory loop,” says Ryan. “These programs are a way to keep farmers and ranchers in compliance with state water quality standards and help them meet personal objectives on their operation.”

Three years ago, Idalou, TX, farmer Ute Becton imple-mented a WQMP. His personal plan involves a drip irrigation system installed on 100 acres.

Since Becton’s drip irrigation system is buried under-ground, there are two major advantages. For one, there is no sur-face runoff containing fertilizers and insecticides, and secondly, fertilizer is applied through irrigation in amounts necessary for his crops. Drip irrigation uses water more efficiently and less fertilizer gets into the water supply through this application.

“I am doing what I can to regulate my own operation now rather than face a government mandate that I must follow,” Becton says.

Since environmental issues always will be a major concern for producers and landowners, many are taking action now before any serious problems arise. Voluntarily implementing a WQMP proves that farmers and ranchers are doing their part in environ-mental protection to prevent a required government mandate.

“Farmers are more environmentally conscious than most people because they work in the environment,” Becton says. “They take care of it and don’t intentionally do anything to harm the land.”

Conferences and educational programs are available to help farmers become more aware of environmental aspects. Different agencies sponsor programs to increase environmental under-standing and assist farmers in dealing with particular issues.

For more information, contact your local soil and water conservation district.